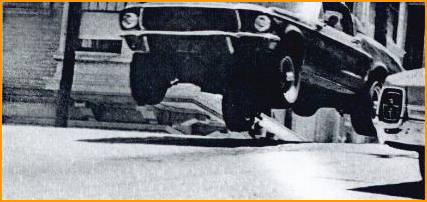

THE GREEN MUSTANG is coming down the steep hill, going fast. A crowded intersection looms up. Still the car picks up speed - it must be doing 60 when it runs the stoplight, booms into the intersection, bounces with terrible impact and keeps going.

And we, the audience, are suddenly hurled into the middle of the wildest car chase ever put on film. The cars bounce, they crash. We are at once repelled by the brutal treatment they receive, startled that their suspensions do not buckle, and amazed that their drivers are able to keep them on four wheels at all.

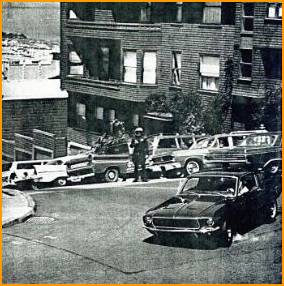

Bullitt, a smash at the box office (it is making millions) and an Oscar winner (for film editing) deals with cops vs. crooks, good vs. evil in San Francisco, the city of hills. "Good" is a very fast, very tenacious Mustang, driven by Steve McQueen (who is awfully tenacious himself). "Evil" is an equally fast, equally tenacious Dodge Charger tooled by two shotgun-toting killers.

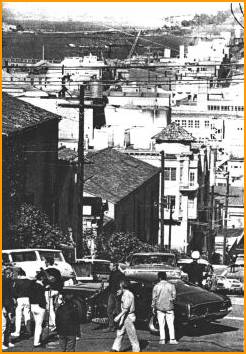

The rip-roaring 110-mph chase up, down and over the top of Frisco's steepest streets has been called art, and art it probably is: Surely no better, or scarier chase sequence has ever reached the screen. On the screen, it lasts 10 minutes or so. The actual filming of it consumed three weeks. This is not trick photography: these are real shots of real cars driven by real men. San Francisco has not seen so much action since the earthquake.

But - to shatter the illusions of his many fans - Steve McQueen did NOT do all the driving

himself...

McQueen "only" did three-quarters of it - nearly everything but those hairraising flat out leaps down Chestnut Avenue. And McQueen might have attempted those, too, had not some highplaced executives stepped in and said, in effect: "McQueen, you have already hired some of the best stuntmen in Hollywood. You can't risk your own neck jumping the hills of San Francisco in a single bound even it you want to."

The mad scramble ends, miles out of San Francisco proper, when McQueen has once pretty Mustang now battered and torn from clouting too many curbs and parked cars, creams the side of the Charger and sends it flying off the road. At 90 it veers head-on into a gas dump for trucks and there follows a thundering explosion and fire. McQueen is more fortunate. His Mustang slews across four lanes of traffic and slams to a stop in a ditch, still on four wheels.

On the surface, Bullitt is a tough detective movie. But beyond that it is a study in destruction. And the Mustang and the Charger, for all the mayhem that is willfully inflicted on them by their drivers, never quit. Astonishingly, they were close to being stock, too, although lots of meticulous work went into their preparation (see the following

page).

It is the jumps, accomplished on the horribly steep San Francisco streets as the cars plunge downhill, often in traffic, which defy belief. The two cars bounce like tops. They are up in the air for 30 feet or more.

The Charger was driven by a stuntman named Bill Hickman, who portrays himself in the film. He has no lines to speak, he just drives like a fiend, and he nearly flipped the heavy Charger as he cannoned down a sheer hill and the brake pedal went to the

floor.

In his path were the camera crew and numerous San Francisco policemen holding back the crowd. Hickman is a professional. He threw the car into a horrendous broadslide and careened round the corner on nerve alone. The cameramen never moved, never stopped shooting. They, too, were pros.

The Mustang was driven by three different men: McQueen himself, who at times reached 110 mph; Carey Loftin, the 50-year-old patriarch of Hollywood stuntmen (he worked with W.C.Fields in the Thirties), who was in charge of all the stunts, and who wrestles the Mustang across the road at the end; and Bud Ekins, a tall gaunt, long-haired professional motorcycle rider and sometime car driver.

Though taller, and with a crop of hair that would delight any hippie, Ekins resembles McQueen somewhat (he doubled for Steve during the motorcycle stunts in The Great Escape). He got the call to do the Mustang jumps. Ekins stood nervously at the top of Chestnut Street, peering down. "It looks like a ski jump", he said. But it was not a sheer hill because everytime there was a cross street. Chestnut would briefly level of. When the intersection ended, Chestnut immediately shot downhill against.

It was when Ekins hit those intersections at 60 that the Mustang bottomed out, groaned, then took off like a bird out into the void. Doing the jumps, all Ekins could see, was the blue sky. Later he described the sensation as "just like driving off the end of the

world."

There were no practice or "dry runs". San Francisco cops, equipped with walkie-talkies, had the side streets roped off, and eight cameras and a crew of 60 were taking in Ekins' every

move.

Ekins walked to the Mustang, revved it up loud, the cameras started to turn... and he burned rubber all the way to the bottom of the hill. The banging and crashing was audible for several city

blocks.

"After the first jump," Ekins shrugs, "it was easy." For his trouble, he was paid as much as $1000 per

day.

Later he drove the Mustang flat out on the open highway, passing cars to keep up with the fleeing Charger, which was bouncing off trucks and the like. Driver Hickmann had to graze the back wheels of a truck, gouge a guardrail - where there was an 800-foot drop-off on the outside - then veer sharply back into line for the camera. The chase was nothing if not authentic. Ekins, subbing for McQueen, had to follow. Other stuntmen were driving cars up the highway during the filming and one of them, a friend of Ekins nearly busted Bud's car headon. "I really made ol' Bud work for his money." The man giggled afterwards. Ekins had to stab the brakes very hard and nearly went through the Mustang's windshield.

Poor Ekins! Having all this happen to him still wasn't enough. The next day McQueen put hin on a motorcycle and told him to go fall off it for the cameras - skilfully of course. The Charger came swerving down the highway at 80 or so, swung out to pass another car, and found Ekins' motorcycle dead ahead. Ekins had to lock up the BSA's back wheel, then slide on his back down the road. The slide carried him 75 feet on the blacktop. The Charger barely missed him. Any bruises? "Nope. None. Nothing to it." (Stuntmen, all stuntmen, never admit, when they are hurt. It hurts their reputations and no director wants to hire them. What is more useless than an injury-prone stuntman?)

Yet of all the Bullitt stuntmen, none had quite as scary a job as that of Tom Steel. The script called for two men to ride in the Charger, which Bill Hickman was slamming of walls and parked cars. Steel was the passenger subbing for the trigger-happy actor in the film. Afterwards Steel admitted that riding with Hickman had unnverved him. It is one thing to do such crazy stunts yourself. It is something else again to have to ride with someone else who is doing them.

Bullitt was filmed during May of 1968, and each night all the stuntmen would gather for drinks and talk at a local hotel. Every night Loftin would put up a blackboard and map out what horrors awaited the men on the

morrow.

The cars, the poor, ever-willing cars also received attention. Mechanics crawled under them, checking for fatigued parts and cracks. Gone undetected, a broken spindle or loose wheel could have been fatal.

For Bullitt was not only the most spectacular car chase ever filmed, it was easily the fastest. On the highway near the waterfront, the cars exceeded 110 mph. The camera car - a flatbed rig with a big Chevy engine - moved alongside and chief cameraman Bill Fraker, his white beard blowing wildly in the wind, zeroed in for a close-up of McQueen at speed. At the same time an elderly man in a passenger car slipped through the police barricade and was cruising down the road at 34mph, when the Charger, the Mustang and the camera car all boomed down on top of him. Somehow, there was no collision- just one very scared old man.

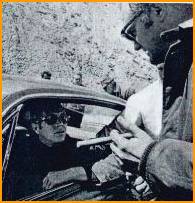

McQueen was everywhere; watching, overseeing, shouting suggestions, demanding authenticity at all times. At first he attempted to drive the Mustang himself (he has a cool touch with fast cars and motorcycles, was promising amateur race driver eight years ago). But Steve is no stuntman. After overshooting a couple of corners, he quit in disgust and gave the car back to Ekins. Yet the sequence where McQueen overshoots the corner and smokes his tires wildly is included in Bullitt - it was so realistic McQueen could not bring himself to leave it

out.

Later, McQueen again climbed into the Mustang: He is the driver when one of the killers turns loose a shotgun and blows out the windshield.

Filming Bullitt was not fun for the stuntmen, it was deadly hard work and risky, but everyone got at least one good laugh. This was the very beginning of the chase, which commences in a crowded four-way intersection. McQueen wanted the traffic to look like real traffic, so he used real traffic.

Ekins, Harris, Drake and the other stuntmen drive unmarked passenger cars and sit in the intersection, blocking traffic and keeping the intersection clear as the stoplights keep changing from green to red. Traffic builds up behind them for blocks. The motorists grow impatient, then angry, and begin honking their horns and cursing. Everyone is mad. Still the stuntmen stubbornly refuse to move, keeping the intersection clear.

Suddenly the Mustang, the Charger and the camera car, all careen through the intersection at top speed, squalling rubber and making a tremendous racket screaming up the hill and out of sight. Then the stunt drivers casually pull away, laughing. Everyone else wonders, what the devil is going on.

No one was injured during the filming, which was astonishing considering the speeds. One expensive camera was destroyed, when Bill Hickman's Charger bobbled on a corner and slammed into it. The footage itself was salvaged and appears int he movie. Some of the other footage never made it to the screen.

The climactic scene, where the Charger plows off the road into the gas station and everything blows up, was the most difficult to film, and the most dissatisfying for those who worked on Bullitt. The scene nearly didn't come off at all, and the set, constructed at a costs of thousands, almost had to be rebuilt so the scene could be repeated. Only superb film editing saved a costly reshooting.

There is a standard technique used in such shots, called "tow and release". Carey Loftin, driving the Mustang, has the Charger (with a dummy behind the wheel) lashed to the side of the Mustang. From a distance, it looks as if the two cars are racing along side by side. As they roar down upon the crash site, Loftin triggers a special release lever inside the Mustang, which turns loose the Charger. Completely driverless, it hurtles down the road, off the road and into the explosion.

But Loftin was towing the Charger too fast - nearly 90mph. The Charger overshot and missed the gas pumps. (This is impossible to spot, when seeing BULLITT for the first time. Seen a second time, you can spot it easily.)

What happened to the cars after the filming?

The Charger, with only 600 miles showing on the odometer, was destroyed in the crash and fire. The Mustang, the Charger's nemesis, survived the filming, although an A-arm in the suspension did let go the final day of filming. The car was repaired, cleaned up, and later sold for $2500. Not a bad price for a movie star.

How they prepared the Cars

Are stock Detroit cars really strong enough to withstand the tortures of Bullitt? Not quite. Both the Mustang and the Charger underwent extensive beefing up at the hands of Max Balchowsky, the veteran sports car racer and builder (remember his Buick "Ol' Yeller"?) before they were turned loose on the San Francisco streets. Balchowsky, who also toiled on the film as a stunt driver, said later, "I had no idea the kind of thing those cars were going to be subjected to. No idea, the jumps were going to be that

rough."